Last year I started painting with oil paints again, after almost a decade of only using acrylic and gouache. I had gotten used to making solid, crisp blocks of color with gouache, and I found myself wondering how I could make a sharp edge with oil paint.

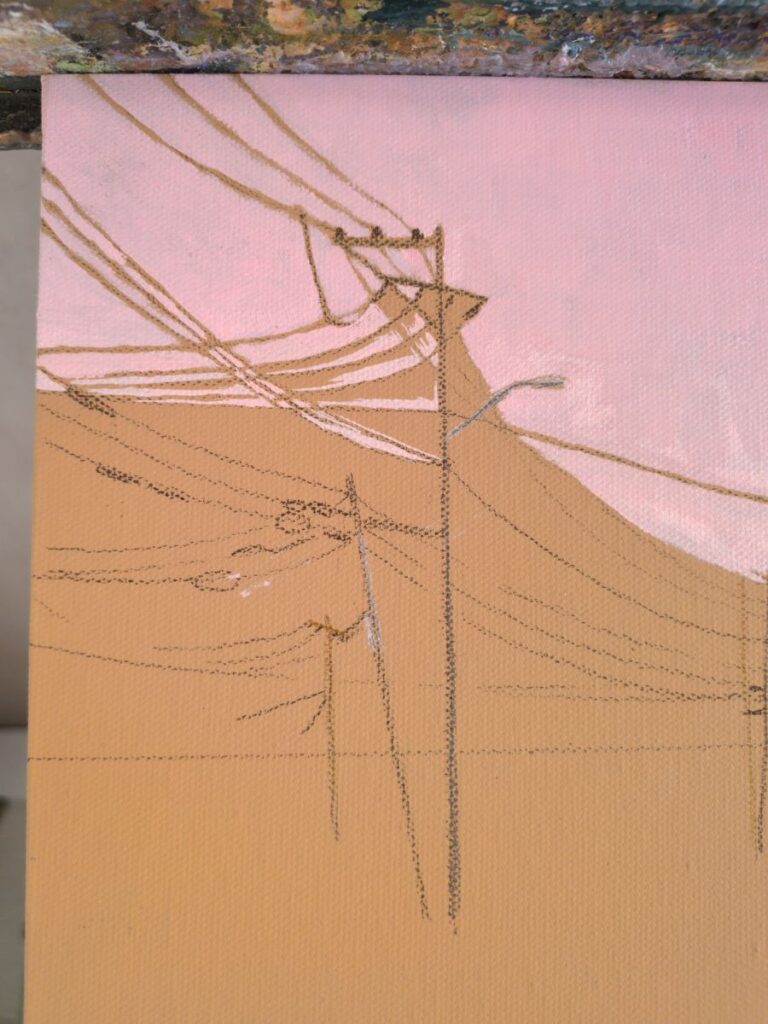

I feel a little silly making a blog post about this, because it’s something I still struggle with, but after a lot of web-searching, forum-reading, and experimentation, I’m getting much cleaner lines and edges than before – as evidenced by the progress photo below, where you can see that the blue shape of the dress is pretty crisp against the magenta underpainting. The curve of the belly especially is much sharper than anything I was getting a year ago! So, here’s a post summarizing what I’ve changed about my painting in my quest to get a crisp, sharp edge with oil paint.

1. Make sure previous layers are dry enough

This is the big one, and the one I didn’t see discussed when I was searching for answers – perhaps it’s obvious to most people! But after some experimenting, I realized that my main problem was that I just wasn’t letting the prior layers dry enough.

My previous experience with oil paint was when taking elective classes in college, and in that setting, we would usually have a week or two to finish an assignment, which meant they could only dry for a couple days in between painting sessions. When I started using oil paint again, it took me a while to realize that I could let paintings sit for much longer, and that in fact, I needed to let them dry for longer if I wanted to get a really sharp edge with the next layer.

Obviously the specific amount of time you have to wait is going to depend on which medium or solvent you use, how much of it you use, how thick your paint is, and even what the temperature/humidity/air circulation is like where you’re storing your paintings, but to get a crisp edge, you want any previous layers of paint to be really dry. Not “well, I guess I can probably paint over this,” not just barely dry to the touch – it needs to be dry enough that the older paint is not going to blend with the new paint (unless you drown it in solvent, which you’re not going to do). I’m now often letting paintings wait for 2 weeks (or even a month) if I want to get a really sharp edge.

3. Rest your hand on your canvas

Since your previous layers are really dry (see tip #1 above), you can rest your hand right on your canvas as you work! This will give you more stability and control. If you plan carefully, working from the center out and rotating, raising, or lowering your canvas as needed, you can probably find a safe place to rest your hand for almost any spot you want to paint. If you’ve got a situation where you really can’t find somewhere to rest your hand, there’s also a tool called a mahlstick that can help (and it’s easy to DIY, I have just used a yardstick and paper towel before).

3. Hold your brush at the correct angle

This is another one that might be obvious to everyone but me, but I’m going to spell it out for anyone else whose intuition is leading them astray!

A paintbrush is not a pencil. When using a flat or bright brush shape, you should not be holding the brush with the line of the tip perpendicular to the edge you want to make and drawing along it with the outer edge of the brush. Although this movement might feel intuitive, it’s not going to make a clean edge because any variation in the pressure of the brush against the canvas is going to spread the bristles out and make your edge wobbly! Instead, you should should be lining up the tip of the brush parallel to the line you want to paint, and then making short strokes away from the edge.

The photos below show an example where I’m filling in a big block of light blue, following the curve of a white line I had previously sketched in. On the left, I’m holding the brush correctly: the end of the brush is tangent to the white line I’m following, and my hand is positioned to make a clean stroke away from the edge I’m creating (although if I wasn’t trying to take a photograph with my other hand, I would probably start even closer to the white line, or even a little on top of it). Lots of little strokes like this will allow me to fill in the shape right up to the line, and leave a very sharp edge. On the right, I am holding my brush incorrectly: if I push down to make a mark, the bristles will spread, and it will be difficult to have enough control to keep them off the white line.

4. Use a round brush for thin, crisp lines

A flat or bright brush works well for making a straight edge or filling in the outside of a curve (as in the example above), but what if you want fill in the inside of a curve? In this situation, if you line up the end of your brush tangent to the edge you want to make, the outside edges of your brush might cross the line you’re trying to follow.

If the curvature isn’t too great, a smaller flat brush might do okay, but if it’s a very small area or a tight curve, you’re going to want to switch to a round brush. With a round brush, you want to use just the tip, and you can go along the edge (like using a pencil).

If you want to make a particularly thin line, having a round brush with especially long hairs helps. I have seen people recommend “rigger” brushes (as far as I know that’s just a long round brush), but I ended up buying a pinstriping brush and a longliner brush by Kafka Design (link to Blick, but I’m sure they’re sold elsewhere too). What I like about these is that they’re designed with short handles, so you can use them with the end of the handle resting on your hand between your thumb and index finger. My hand is not as steady as I wish it was, and I find that holding the brush that way helps.

If you look near the middle of the photo below (or a little bit up from the middle), you can find a very, very thin pink line that I painted with my Kafka Design longliner brush. This is a closeup photo of an 8 inch by 10 inch panel (the sketched in lines were made by recently sharpened colored pencil), so that pink line is incredibly thin. I’m still working on getting the consistent pressure needed to make a constantt line width, but I do think these long hair / short handle brushes were a big upgrade.

5. Use tape

It’s pretty common to see acrylic painters use masking tape to get extra crisp, straight lines – turns out, you can actually do that with oil paint too! I haven’t tried putting tape straight on a prepared canvas or panel, and I suspect it wouldn’t work well on top of thick textured paint, but masking tape on top of a thin, dry layer of oil paint has worked fine for me. Just make sure your previous layers are extremely dry before putting it on (funny how this whole blog post comes back to that one tip…), and take it off as soon as you can.